The news media plays a key role in shaping public perception about artificial intelligence. Since 2017, when Ottawa launched its Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy, AI has been hyped as a key resource for the Canadian economy.

With greater than $1 billion in public funding committed, the federal government presents AI as having potential that have to be harnessed. Publicly-funded initiatives, like Scale AI and Forum IA Québec, exist to actively promote AI adoption across all sectors of the economy.

Over the last two years, our multi-national research team, Shaping AI, has analyzed how mainstream Canadian news media covers AI. We analyzed newspaper coverage of AI between 2012 and 2021 and conducted interviews with Canadian journalists who reported on AI during this time period.

Our report found news media closely reflects business and government interests in AI by praising its future capabilities and under-reporting the facility dynamics behind these interests.

The chosen few

Our research found that tech journalists are inclined to interview the identical pro-AI experts over and another time — especially computer scientists. As one journalist explained to us: “Who is the perfect person to discuss AI, apart from the one who is definitely making it?” When a small variety of sources informs reporting, news stories usually tend to miss vital pieces of data or be biased.

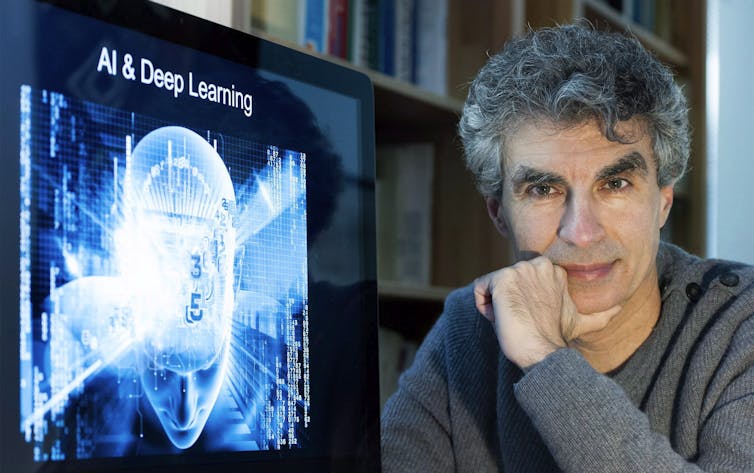

Canadian computer scientists and tech entrepreneurs Yoshua Bengio, Geoffrey Hinton, Jean-François Gagné and Joëlle Pineau are disproportionately used as sources in mainstream media. The name of Bengio — a number one expert in AI, pioneer in deep learning and founding father of Mila AI Institute — turns up nearly 500 times in 344 different news articles.

Only a handful of politicians and tech leaders, like Elon Musk or Mark Zuckerberg, have appeared more often across AI news stories than these experts.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Chris Young

Few critical voices find their way into mainstream coverage of AI. The most-cited critical voice against AI is late physicist Stephen Hawking, with only 71 mentions. Social scientists are conspicuous of their absence.

Bengio, Hinton and Pineau are computer science authorities, but like other scientists they’re not neutral and freed from bias. When interviewed, they advocate for the event and deployment of AI. These experts have invested their skilled lives in AI development and have a vested interest in its success.

AI researchers and entrepreneurs

Most AI scientists aren’t only researchers, but are also entrepreneurs. There is a distinction between these two roles. While a researcher produces knowledge, an entrepreneur uses research and development to draw investment and sell their innovations.

The lines between the state, the tech industry and academia are increasingly porous. Over the last decade in Canada, state agencies, private and public organizations, researchers and industrialists have worked to create a profitable AI ecosystem. AI researchers are firmly embedded on this tightly-knit network, sharing their time between publicly-funded labs and tech giants like Meta.

AI researchers occupy key positions of power in organizations that promote AI adoption across industries. Many hold, or have held, decision-making positions at the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) — a corporation that channels public funding to AI Research Chairs across Canada.

When computer scientists make their way into the news cycle, they accomplish that not only as AI experts, but additionally as spokespeople for this network. They bring credibility and legitimacy to AI coverage due to their celebrated expertise. But also they are ready to advertise their very own expectations in regards to the way forward for AI, with little to no accountability for the fulfilment of those visions.

Hyping responsible AI

The AI experts quoted in mainstream media rarely discussed the technicalities of AI research. Machine learning techniques — colloquially often known as AI — were deemed too complex for a mainstream audience. “There’s only room for therefore much depth about technical issues,” one journalist told us.

Instead, AI researchers use media attention to shape public expectations and understandings of AI. The recent coverage of an open letter calling for a six-month ban on AI development is a superb example. News reports centred on alarmist tropes on what AI could turn into, citing “profound risks to society.”

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Graham Hughes

Bengio, who signed the letter, warned that AI has the potential to destabilize democracy and the world order.

These interventions shaped the discourse about AI in two ways. First, they framed AI debates based on alarmist visions of distant future. Coverage of an open letter calling for a six-month break from AI development overshadowed real and well-documented harms from AI, like employee exploitation, racism, sexism, disinformation and concentration of power within the hands of tech giants.

Second, the open letter casts AI research right into a Manichean dichotomy: the bad version that “nobody…can understand, predict, or reliably control” and the nice one — the so-called responsible AI. The open letter was as much about shaping visions in regards to the way forward for AI because it was about hyping up responsible AI.

But based on AI industry standards, what’s framed as “responsible AI” up to now has consisted of vague, voluntary and toothless principles that can not be enforced in corporate contexts. Ethical AI is usually only a marketing ploy for profit and does little to eliminate the systems of exploitation, oppression and violence which can be already linked to AI.

Report’s recommendations

Our report proposes five recommendations to encourage reflexive, critical and investigative journalism in science and technology, and pursue stories in regards to the controversies of AI.

1. Promote and put money into technology journalism. Be wary of economic framings of AI and investigate other angles which can be typically unnoticed of business reporting, like inequalities and injustices brought on by AI.

2. Avoid treating AI as a prophecy. The expected realizations of AI in the long run have to be distinguished from its real-world accomplishments.

3. Follow the cash. Canadian legacy media has paid little attention to the numerous amount of governmental funding that goes into AI research. We urge journalists to scrutinize the networks of individuals and organizations that work to construct and maintain the AI ecosystem in Canada.

4. Diversify your sources. Newsrooms and journalists should diversify their sources of data with regards to AI coverage. Computer scientists and their research institutions are overwhelmingly present in AI coverage in Canada, while critical voices are severely lacking.

5. Encourage collaboration between journalists and newsrooms and data teams. Co-operation amongst various kinds of expertise helps to spotlight the social and technical considerations of AI. Without one or the opposite, AI coverage is prone to be deterministic, inaccurate, naive or overly simplistic.

To be reflexive and significant of AI doesn’t mean to be the event and deployment of AI. Rather, it encourages the news media and its readers to query the underlying cultural, political and social dynamics that make AI possible, and examine the broader impact that technology has on society and vice versa.

This article was originally published at theconversation.com