When giant blobs began appearing on city skylines all over the world within the late Nineteen Eighties and Nineteen Nineties, it marked not an alien invasion however the impact of computers on the practice of constructing design.

Thanks to computer-aided design (CAD), architects were capable of experiment with recent organic forms, free from the restraints of slide rules and protractors. The result was famous curvy buildings corresponding to Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao and Future Systems’ Selfridges Department Store in Birmingham.

Today, computers are poised to vary buildings once more, this time with algorithms that may inform, refine and even create recent designs. Even weirder shapes are only the beginning: algorithms can now work out the perfect ways to put out rooms, construct the buildings and even change them over time to satisfy users’ needs. In this fashion, algorithms are giving architects a complete recent toolbox with which to grasp and improve their ideas.

At a basic level, algorithms generally is a powerful tool for providing exhaustive information for the design, construction and use of a constructing. Building information modelling uses comprehensive software to standardise and share data from across architecture, engineering and construction that was held individually. This means everyone involved in a constructing’s genesis, from clients to contractors, can work together on the identical 3D model seamlessly.

More recently, recent tools have begun to mix this sort of information with algorithms to automate and optimise elements of the constructing process. This ranges from interpreting regulations and providing calculations for structural evaluations to creating procurement more precise.

Algorithmic design

But algorithms may help with the design stage, helping architects to know how a constructing will likely be utilized by revealing hidden patterns in existing and proposed constructions. These may be spatial and geometrical characteristics corresponding to the ratio of public to personal areas or the natural airflow of a constructing. They may be patterns of use showing which rooms are used most and least often.

Or they may be visual and physical connections that show what people can and may’t see from each point of a constructing and enable us to predict the flow of individuals around it. This is especially relevant when designing the entrances of public buildings so we will place services and escape routes in the perfect position.

Algorithms will also be used to increase the aptitude of designers to take into consideration and generate shapes and arrangements which may not otherwise be possible. Instead of personally drawing floor plans in accordance with their intuition and taste, architects using algorithmic design input the foundations and parameters and permit the pc to supply the form of the constructing. These algorithms are sometimes inspired by ideas from nature, corresponding to evolution or fractals (shapes that repeat themselves at ever smaller scales).

Zaha Hadid Architects

Combining these three uses (managing complex information, revealing patterns and generating recent spatial arrangements) represents the following generation of algorithmic design that can really change our ability to enhance the built environment. For example, Zaha Hadid Architects, already known for its unusual curvy constructions, uses algorithms to routinely test 1000’s of internal layout options or find an arrangement of facade panels that can prevent an irregularly shaped constructing from being prohibitively expensive.

Algorithms are also essential to novel constructions, corresponding to the Filament Pavilion on the V&A museum, and adapted over time in response to structural, environmental and visitor usage data. Today, algorithms are even producing office arrangements for the COVID-19 pandemic that enable the best variety of employees to work in a constructing while safely socially distancing.

Self-organising layouts

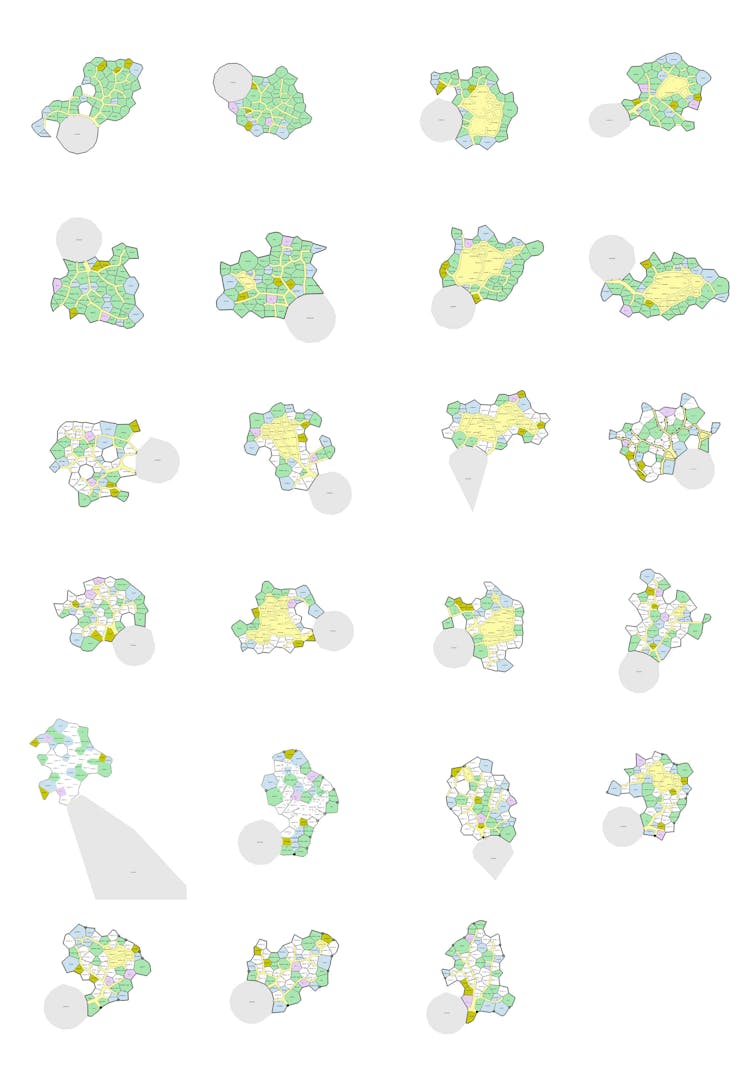

My colleagues and I recently showed how algorithms could create a self-organising floorplan for a care home, laying out the rooms in the perfect configuration to enhance the experience of dementia patients. To do that we combined three kinds of algorithm, inspired respectively by ant colonies, artificial intelligence systems based on the brain, and crowd modelling.

We built our algorithms to follow design criteria based on quite a few previous studies and projects, condensing them into 4 most important rules for the algorithms to follow. The constructing needed to be divided into units of maximum given sizes. And each unit needed to have an accessible functional kitchen, a dining room not used for other activities, and multiple lounges or activity rooms of a wide range of sizes.

Silvio Carta, Tommaso Turchi, Stephanie St Loe and Joel Simon, Author provided

The result was a brand new layout for a care home that arranged private rooms and customary areas in probably the most convenient option to make residents’ journeys across the home as short as possible. This shows how the proper combination algorithms and, crucially, input from designers will help produce self-organising designs that might otherwise require an enormous amount of laborious work or which may otherwise not be possible.

Rather than replacing architects, as some have pessimistically predicted, algorithms have gotten a crucial tool for constructing designers. This is reflected within the technology’s growing prominence in postgraduate courses, research centres and international firms. More and more we see designers investing in the usage of machine learning and artificial intelligence in architecture.

As advancements in computer science and technology are growing exponentially, it’s difficult to assume now how algorithmic design will evolve in the long run and the way the constructing industry will change. But we will definitely predict that we the usage of algorithms will soon be an ordinary way of augmenting our ability to see the invisible and design the unthought in our buildings.

This article was originally published at theconversation.com