Klaus Schwab, the founding father of the World Economic Forum, argues that the only most vital challenge facing humanity today is the way to understand and shape the brand new technology revolution. What exactly is that this revolution, and why does it matter, especially for Africa?

The “fourth industrial revolution” captures the thought of the confluence of recent technologies and their cumulative impact on our world.

Artificial intelligence can produce a medical diagnosis from an x-ray faster than a radiologist and with pinpoint accuracy. Robots can manufacture cars faster and with more precision than assembly line employees. They can potentially mine base metals like platinum and copper, crucial ingredients for renewable energy and carbon cleansing technologies.

3D printing will change manufacturing business models in almost inconceivable ways. Autonomous vehicles will change traffic flows by avoiding bottlenecks. Remote sensing and satellite imagery may help to locate a blocked storm water drain inside minutes and avoid city flooding. Vertical farms could solve food security challenges.

The machines are still learning. But with human help they may soon be smarter than us.

The first industrial revolution spanned 1760 to 1840, epitomised by the steam engine. The second began within the late nineteenth century and made mass production possible. The third began within the Nineteen Sixties with mainframe computing and semi-conductors.

The argument for a brand new category – a fourth industrial revolution – is compelling. New technologies are developing with exponential velocity, breadth and depth. Their systemic impact is more likely to be profound. Policymakers, academics and firms must understand why all these advances matter and what to do about them.

So why does the fourth industrial revolution matter a lot – specifically for Africa? And how should the continent approach the risks and opportunities?

Exciting opportunities

The revolution’s most fun dimension is its ability to deal with negative externalities – hidden environmental and social costs. As Schwab has written:

Rapid technological advances in renewable energy, fuel efficiency and energy storage not only make investments in these fields increasingly profitable, boosting GDP growth, but in addition they contribute to mitigating climate change, one among the key global challenges of our time.

Some countries’ growth trajectories may follow the hypothesised Environmental Kuznets Curve, where income growth generates environmental degradation. This is partly because natural capital is treated as free, and carbon emission as costless, in our global national accounting systems.

New technologies make it possible to truncate this curve. It becomes possible to transition to a “circular economy”, which decouples production from natural resource constraints. Nothing that’s made in a circular economy becomes waste. The “Internet of Things” allows us to trace material and energy flows to realize recent efficiencies along product value chains. Even the way in which energy itself is generated and distributed will change radically, relying less and fewer on fossil fuels.

Perhaps most significantly for African countries, then, renewable energy offers the potential of devolved, deep and broad access to electricity. Many have still not enjoyed the advantages of the second industrial revolution. The fourth may finally deliver electricity since it not relies on centralised grid infrastructure. A wise grid can distribute power efficiently across a variety of homes in very distant locations. Children will give you the option to check at night. Meals will be cooked on secure stoves. Indoor air pollution can mainly be eradicated.

Beyond renewable energy, the Internet of Things and blockchain technology forged a vision for financial inclusion that has long been elusive or subject to exploitative practices.

Risks

No revolution comes without risks. One on this case is rising joblessness.

Developing countries have moved away from manufacturing into services long before their more developed counterparts did, and at fractions of the income per capita. Dani Rodrik calls this process “premature deindustrialisation”.

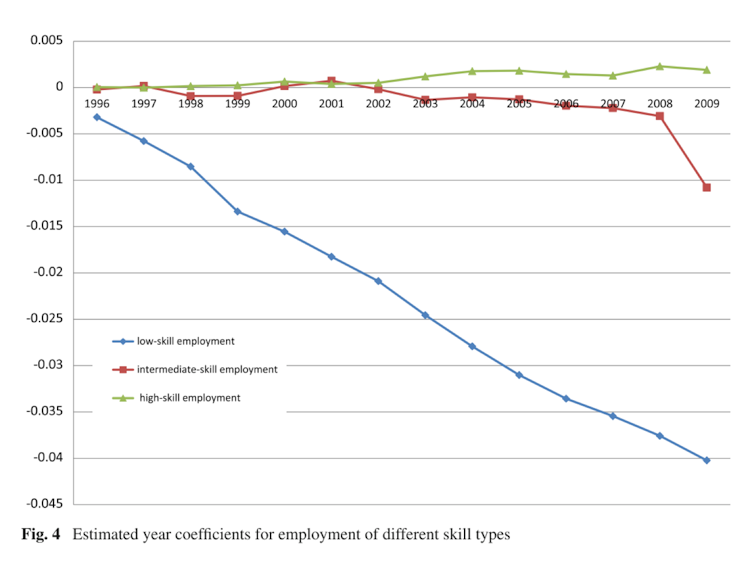

The employment shares of producing, together with its value addition to the economy, has long been declining in industrialised nations. But it’s also been declining in developing countries. This is unexpected, because manufacturing remains to be the first channel through which to modernise, create employment (especially by absorbing unskilled labour) and alleviate poverty. Manufacturing industries that were built up under a wall of post-independence protectionism are beginning to decompose.

Rodrik D, ‘Premature deindustrialisation’, Journal of Economic Growth, 21, 2016, p. 19.

The social effects of joblessness are devastating. Demographic modelling indicates that Africa’s population is growing rapidly. For optimists this implies a “dividend” of young producers and consumers. For pessimists, it means a growing problem of youth unemployment colliding with poor governance and weak institutions.

New technologies threaten to amplify current inequalities, each inside and between countries. Mining – typically a big employer – may change into more characterised by keyhole than open heart surgery, to borrow a medical metaphor. That means driverless trucks and robots, all fully digitised, conducting non-invasive mining. A big proportion of the nearly 500 000 people employed in South African mining alone may stand to lose their jobs.

Rising inequality and income stagnation are also socially problematic. Unequal societies are inclined to be more violent, have higher incarceration rates, and have lower levels of life expectancy than their more equal counterparts.

New technologies may further concentrate advantages and value within the hands of the already wealthy. Those who didn’t profit from earlier industrialisation risk being left even further behind.

So how can African countries make sure that they harness this revolution while mitigating its risks?

Looking ahead

African countries should avoid a proclivity back towards the import substitution industrialisation programmes of early independence. The answer to premature deindustrialisation just isn’t to guard infant industries and manufacture expensively at home. Industrialisation within the twenty first century has a very different ambience. In policy terms, governments have to employ systems pondering, operating in concert moderately than in silos.

Rapidly improving access to electricity ought to be a key policy priority. Governments should view energy security as a function of investment in renewables and the muse for future growth.

More generically, African governments ought to be proactive in adopting recent technologies. To do so that they must stand firm against potential political losers who form barriers to economic development. It pays – within the long-run – to craft inclusive institutions that promote widespread innovation.

There are serious benefits to being a primary mover in technology. Governments ought to be constructing clear strategies that entail all the advantages of a fourth industrial revolution. If not, they risk being left behind.

This article was originally published at theconversation.com