Whether artificial intelligence systems steal humans’ jobs or create recent work opportunities, people might want to work along with them.

In my research I exploit sensors and computers to observe how the brain itself processes decision-making. Together with one other brain-computer interface scholar, Riccardo Poli, I checked out one example of possible human-machine collaboration – situations when police and security staff are asked to maintain a lookout for a specific person, or people, in a crowded environment, resembling an airport.

It looks as if a simple request, nevertheless it is definitely really hard to do. A security officer has to observe several surveillance cameras for a lot of hours every single day, on the lookout for suspects. Repetitive tasks like these are vulnerable to human errors.

Some people suggest these tasks should be automated, as machines don’t get bored, drained or distracted over time. However, computer vision algorithms tasked to acknowledge faces could also make mistakes. As my research has found, together, machines and humans could do a lot better.

Two sorts of artificial intelligence

We have developed two AI systems that might help discover goal faces in crowded scenes. The first is a facial recognition algorithm. It analyzes images from a security camera, identifies which parts of the pictures are faces and compares those faces with a picture of the person who is sought. When it identifies a match, this algorithm also reports how sure it’s of that call.

The second system is a brain-computer interface that uses sensors on an individual’s scalp, on the lookout for neural activity related to confidence in decisions.

ChokePoint data, NICTA

We conducted an experiment with 10 human participants, showing each of them 288 pictures of crowded indoor environments. Each picture was shown for under 300 milliseconds – about so long as it takes an eye fixed to blink – after which the person was asked to determine whether or not that they had seen a specific person’s face. On average, they were capable of accurately discriminate between images with and without the goal in 72 percent of the pictures.

When our entirely autonomous AI system performed the identical tasks, it accurately classified 84 percent of the pictures.

Human-AI collaboration

All the humans and the standalone algorithm were seeing the identical images, so we sought to enhance the decision-making by combining the actions of multiple of them at a time.

Davide Valeriani and Eleonora Adami, CC BY-ND

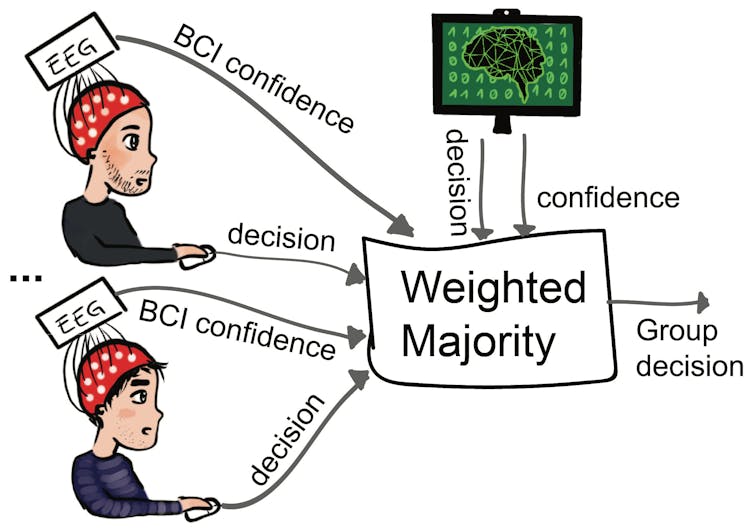

To merge several decisions into one, we weighted individual responses by decision confidence – the algorithm’s self-estimated confidence, and the measurements from the humans’ brain readings, transformed with a machine-learning algorithm. We found that a mean group of just humans, no matter how large the group was, did higher than the typical human alone – but was less accurate than the algorithm alone.

However, groups that included no less than five people and the algorithm were statistically significantly higher than humans or machine alone.

Keeping people within the loop

Pairing individuals with computers is getting easier. Accurate computer vision and image processing software programs are common in airports and other situations. Costs are dropping for consumer systems that read brain activity, and so they provide reliable data.

Working together may help address concerns in regards to the ethics and bias of algorithmic decisions, in addition to legal questions on accountability.

In our study, the humans were less accurate than the AI. However, the brain-computer interfaces observed that the people were more confident about their selections than the AI was. Combining those aspects offered a useful mixture of accuracy and confidence, through which humans often influenced the group decision greater than the automated system did. When there isn’t a agreement between humans and AI, it’s ethically simpler to let humans resolve.

Our study has found a way through which machines and algorithms don’t have to – and in truth mustn’t – replace humans. Rather, they will work along with people to seek out the very best of all possible outcomes.

This article was originally published at theconversation.com