Some weeks ago, a nine-year-old macaque monkey called Pager successfully played a game of Pong with its mind.

While it might sound like science fiction, the demonstration by Elon Musk’s neurotechnology company Neuralink is an example of a brain-machine interface in motion (and has been done before).

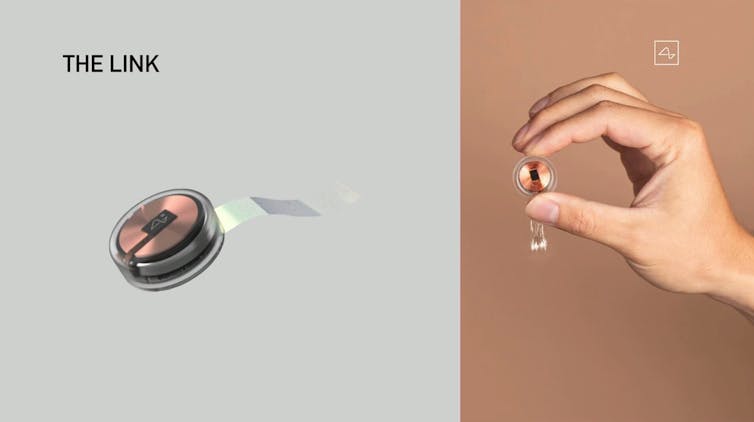

A coin-sized disc called a “Link” was implanted by a precision surgical robot into Pager’s brain, connecting 1000’s of micro threads from the chip to neurons liable for controlling motion.

Brain-machine interfaces could bring tremendous profit to humanity. But to enjoy the advantages, we’ll need to administer the risks all the way down to a suitable level.

A perplexing game of Pong

Screenshot/Youtube

Pager was first shown the right way to play Pong in the standard way, using a joystick. When he made an accurate move, he’d receive a sip of banana smoothie. As he played, the Neuralink implant recorded the patterns of electrical activity in his brain. This identified which neurons controlled which movements.

The joystick could then be disconnected, after which Pager played the sport using only his mind — doing so like a boss.

This Neuralink demo built on an earlier one from 2020, which involved Gertrude the Pig. Gertrude had the Link installed and output recorded, but no specific task was assessed.

Helping individuals with brain injury

According to Neuralink, its technology could help people who find themselves paralysed with spinal or brain injuries, by giving them the power to manage computerised devices with their minds. This would offer paraplegics, quadriplegics and stroke victims the liberating experience of doing things by themselves again.

Prosthetic limbs may also be controlled by signals from the Link chip. And the technology would have the option to send signals back, making a prosthetic limb feel real.

Cochlear implants already do that, converting external acoustic signals into neuronal information, which the brain translates into sound for the wearer to “hear”.

Neuralink has also claimed its technology could treatment depression, addiction, blindness, deafness and a variety of other neurological disorders. This could be done by utilizing the implant to stimulate areas of the brain related to these conditions.

A game-changer

Brain-machine interfaces could even have applications beyond the therapeutic. For a start, they may offer a much faster way of interacting with computers, in comparison with methods that involve using hands or voice.

A user could type a message on the speed of and never be limited by thumb dexterity. They’d only should think the message and the implant could convert it to text. The text could then be played through software that converts it to speech.

Perhaps more exciting is a brain-machine interface’s ability to attach brains to the cloud and all its resources. In theory, an individual’s own “native” intelligence could then be augmented on demand by accessing cloud-based artificial intelligence (AI).

Human intelligence may very well be greatly multiplied by this. Consider for a moment if two or more people wirelessly connected their implants. This would facilitate a high-bandwidth exchange of images and concepts from one to the opposite.

In doing so that they could potentially exchange more information in just a few seconds than would take minutes, or hours, to convey verbally.

But some experts remain sceptical about how well the technology will work, once it’s applied to humans for more complex tasks than a game of Pong. Regarding Neuralink, Anna Wexler, a professor of medical ethics and health policy on the University of Pennsylvania, said:

neuroscience is much from understanding how the mind works, much less having the power to decode it.

Can Neuralink be hacked?

At the identical time, concerns about such technology’s potential harm proceed to occupy brain-machine interface researchers.

Without bulletproof security, it’s possible hackers could access implanted chips and cause a malfunction or misdirection of its actions. The consequences may very well be fatal for the victim.

Some may worry powerful artificial AI working through a brain-machine interface could overwhelm and take control of the host brain.

The AI could then impose a master-slave relationship and, the following thing you understand, humans could develop into a military of drones. Elon Musk himself is on record saying artificial intelligence poses an existential threat to humanity.

He says humans might want to eventually merge with AI, to remove the “existential threat” advanced AI could present:

My assessment about why AI is missed by very smart people is that very smart people don’t think a pc can ever be as smart as they’re. And that is hubris and clearly false.

Musk has famously compared AI research and development with “summoning the demon”. But what can we reasonably make of this statement? It may very well be interpreted as an try to scare the general public and, in so doing, pressure governments to legislate strict controls over AI development.

Musk himself has needed to negotiate government regulations governing the operations of autonomous and aerial vehicles corresponding to his SpaceX rockets.

Hasten slowly

The crucial challenge with any potentially volatile technology is to devote enough effort and time into constructing safeguards. We’ve managed to do that for a variety of pioneering technologies, including atomic energy and genetic engineering.

Autonomous vehicles are a more moderen example. While research has shown the overwhelming majority of road accidents are attributed to driver behaviour, there are still situations through which AI controlling a automobile won’t know what to do and will cause an accident.

Years of effort and billions of dollars have gone into making autonomous vehicles secure, but we’re still not quite there. And the travelling public won’t be using autonomous cars until the specified safety levels have been reached. The same standards must apply to brain-machine interface technology.

It is feasible to plot reliable security to forestall implants from being hacked. Neuralink (and similar corporations corresponding to NextMind and Kernel) have every reason to place on this effort. Public perception aside, they might be unlikely to get government approval without it.

Last yr the US Food and Drug Administration granted Neuralink approval for “breakthrough device” testing, in recognition of the technology’s therapeutic potential.

Moving forward, Neuralink’s implants should be easy to repair, replace and take away within the event of malfunction, or if the wearer wants it removed for any reason. There must even be no harm caused, at any point, to the brain.

While brain surgery sounds scary, it has been around for several a long time and could be done safely.

Neuralink

When will human trials start?

According to Musk, Neuralink’s human trials are set to start towards the top of this yr. Although details haven’t been released, one would imagine these trials will construct on previous progress. Perhaps they may aim to assist someone with spinal injuries walk again.

The neuroscience research needed for such a brain-machine interface has been advancing for several a long time. What was lacking was an engineering solution that solved some persistent limitations, corresponding to having a wireless connection to the implant, reasonably than physically connecting with wires.

On the query of whether Neuralink overstates the potential of its technology, one can look to Musk’s record of delivering leads to other enterprises (albeit after delays).

The path seems clear for Neuralink’s therapeutic trials to go ahead. More grandiose predictions, nonetheless, should stay on the backburner for now.

A human-AI partnership could have a positive future so long as humans remain on top of things. The best chess player on Earth is just not an AI, nor a human. It’s a human-AI team referred to as a Centaur.

And this principle extends to each field of human endeavour AI is making inroads into.

This article was originally published at theconversation.com