The COVID-19 pandemic has caused industrial activity to shut down and cancelled flights and other journeys, slashing greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution around the globe. If there’s something positive to take from this terrible crisis, it could possibly be that it’s offered a taste of the air we would breathe in a low-carbon future.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that about 3 million people die every year from ailments attributable to air pollution, and that greater than 80% of individuals living in urban areas are exposed to air quality levels that exceed secure limits. The situation is worse in low-income countries, where 98% of cities fail to satisfy WHO air quality standards.

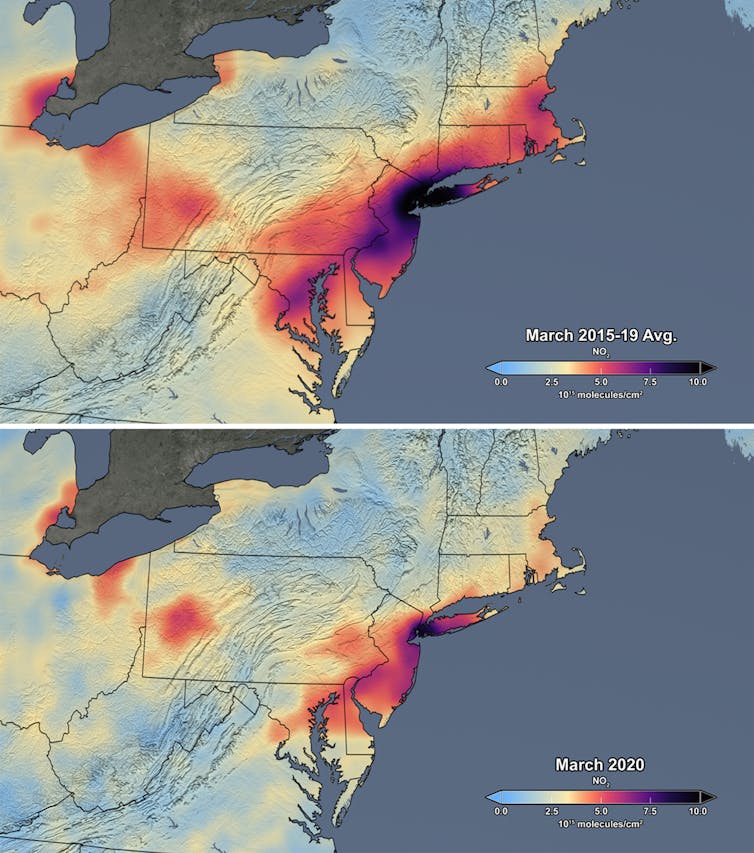

Measurements from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-5P satellite show that in late January and early February 2020, levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) over cities and industrial areas in Asia and Europe were lower than in the identical period in 2019, by as much as 40%.

ESA/NASA, Author provided

Two weeks after the nationwide lockdown was announced on March 23 within the UK, NO₂ pollution in some cities fell by as much as 60% in comparison with the identical period in 2019. NASA revealed that NO₂ pollution over New York and other major metropolitan areas in north-eastern USA was 30% lower in March 2020, in comparison with the monthly average from 2015 to 2019.

Most NO₂ comes from road transport and power plants, and it could possibly exacerbate respiratory illnesses similar to asthma. It also makes symptoms worse for those affected by lung or heart conditions. NO₂ emissions have been a very thorny problem for Europe, with many countries in breach of EU limits.

In a way, we’re conducting the biggest ever global air pollution experiment. Over a comparatively short time frame, we’re turning off major air pollutant sources in industry and transport. In Wuhan alone, 11 million people were in lockdown at the peak of the outbreak there. Across China, over half a billion. China normally emits in excess of 30 mega tonnes of nitrogen oxides per yr, with estimates for 2019 reaching 40 mega tonnes.

EPA-EFE/NASA

Making air quality improvements everlasting

China emits over 50% of all of the nitrogen dioxide in Asia. Each tonne of NO₂ that isn’t emitted in consequence of the pandemic is the equivalent of removing 62 cars per yr from the road. So you may estimate that over China, even a moderate 10% reduction in NO₂ emissions is akin to taking 48,000 cars off the road. But the 40% drop in NO₂ on 2019 levels for January and February in some areas equates to removing a whopping 192,000 cars.

That’s a sign of what could possibly be achieved permanently for air quality if automotive use was phased down and replaced with electrically powered mass transit. Electrifying transport in this fashion, with expanded train lines and more electric cars and charging stations, would slash tail pipe emission of air pollutants similar to NO₂.

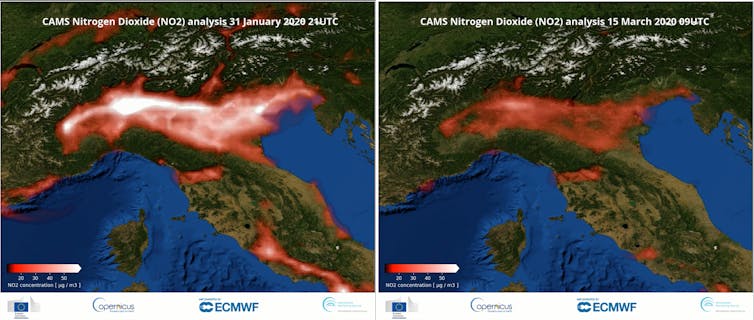

Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS); ECMWF, Author provided

But electric vehicles are only as clean because the electricity that powers them. The recent improvements in air quality could possibly be made everlasting by replacing fossil fuel generation with renewable energy and other low-carbon sources. Reducing monthly NO₂ emissions from electricity generation by 10% could be the equivalent of turning off 500 coal power stations for a yr.

Ironically, by shutting down swaths of the worldwide economy, COVID-19 has helped expose one other respiratory health crisis. The ensuing lockdowns have shown the improvements to air quality which can be possible when emissions are reduced on a worldwide scale.

The pandemic could show us how the long run might look with less air pollution, or it might just indicate the size of the challenge ahead. At the very least, it should challenge governments and businesses to think about how things may be done in a different way after the pandemic, to carry on to temporary improvements in air quality.

This article was originally published at theconversation.com