An art prize on the Colorado State Fair was awarded last month to a piece that – unbeknown to the judges – was generated by a man-made intelligence (AI) system.

Social media have also seen an explosion of weird images generated by AI from text descriptions, similar to “the face of a shiba inu blended into the side of a loaf of bread on a kitchen bench, digital art”.

Or perhaps “A sea otter within the kind of ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’ by Johannes Vermeer”:

OpenAI

You could also be wondering what’s happening here. As any individual who researches creative collaborations between humans and AI, I can inform you that behind the headlines and memes a fundamental revolution is under way – with profound social, artistic, economic and technological implications.

How we came

You could say this revolution began in June 2020, when an organization called OpenAI achieved a giant breakthrough in AI with the creation of GPT-3, a system that may process and generate language in way more complex ways than earlier efforts. You can have conversations with it about any topic, ask it to put in writing a research article or a story, summarise text, write a joke, and do almost any possible language task.

In 2021, a few of GPT-3’s developers turned their hand to pictures. They trained a model on billions of pairs of images and text descriptions, then used it to generate latest images from latest descriptions. They called this method DALL-E, and in July 2022 they released a much-improved new edition, DALL-E 2.

Like GPT-3, DALL-E 2 was a significant breakthrough. It can generate highly detailed images from free-form text inputs, including details about style and other abstract concepts.

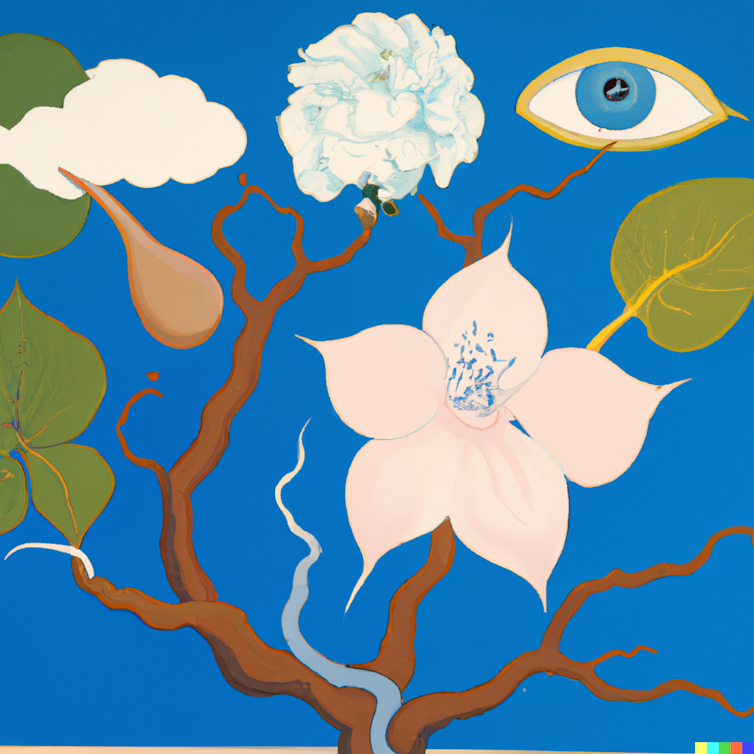

For example, here I asked it as an instance the phrase “Mind in Bloom” combining the types of Salvador Dalí, Henri Matisse and Brett Whiteley.

Rodolfo Ocampo / DALL-E

Competitors enter the scene

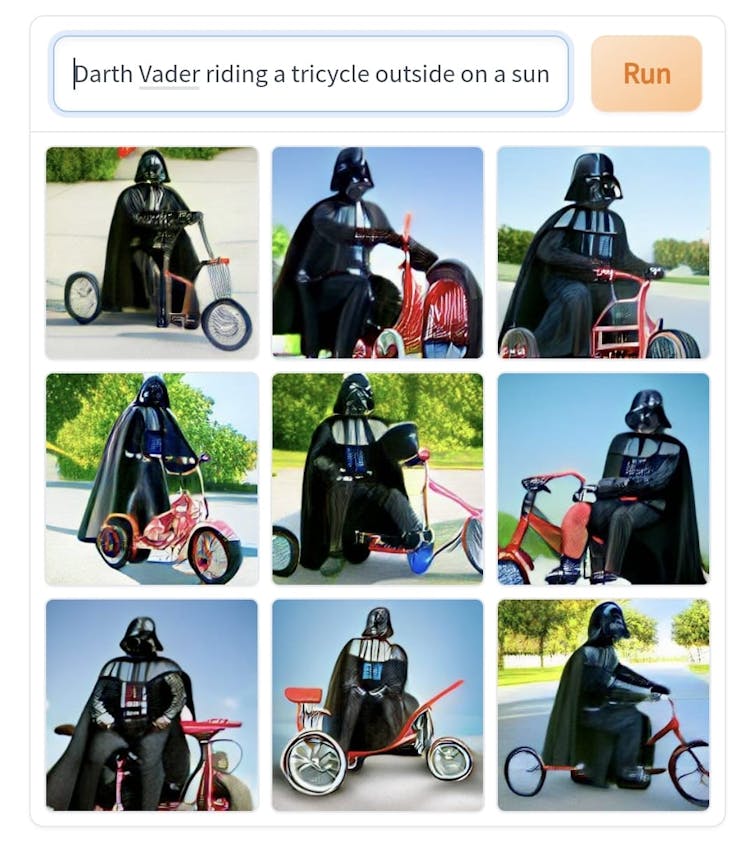

Since the launch of DALL-E 2, a number of competitors have emerged. One is the free-to-use but lower-quality DALL-E Mini (developed independently and now renamed Craiyon), which was a preferred source of meme content.

Craiyon

Around the identical time, a smaller company called Midjourney released a model that more closely matched DALL-E 2’s capabilities. Though still a bit of less capable than DALL-E 2, Midjourney has lent itself to interesting artistic explorations. It was with Midjourney that Jason Allen generated the artwork that won the Colorado State Art Fair competition.

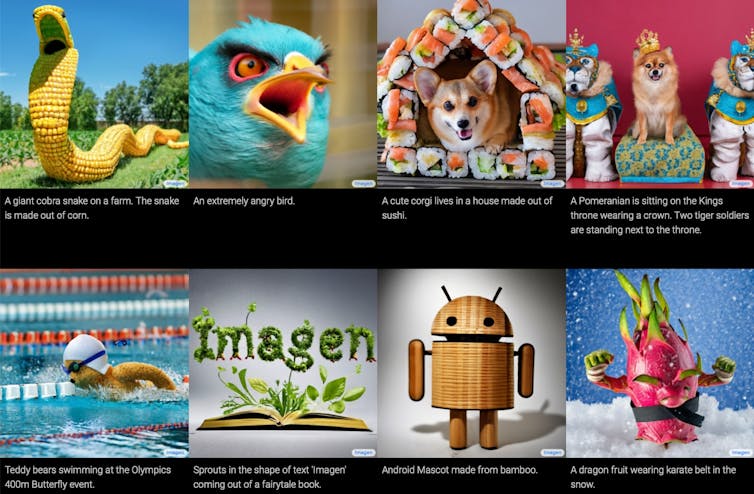

Google too has a text-to-image model, called Imagen, which supposedly produces significantly better results than DALL-E and others. However, Imagen has not yet been released for wider use so it’s difficult to guage Google’s claims.

Google / Imagen

In July 2022, OpenAI began to capitalise on the interest in DALL-E, announcing that 1 million users can be given access on a pay-to-use basis.

However, in August 2022 a brand new contender arrived: Stable Diffusion.

Stable Diffusion not only rivals DALL-E 2 in its capabilities, but more importantly it’s open source. Anyone can use, adapt and tweak the code as they like.

Already, within the weeks since Stable Diffusion’s release, people have been pushing the code to the boundaries of what it will probably do.

To take one example: people quickly realised that, because a video is a sequence of images, they may tweak Stable Diffusion’s code to generate video from text.

Another fascinating tool built with Stable Diffusion’s code is Diffuse the Rest, which permits you to draw an easy sketch, provide a text prompt, and generate a picture from it. In the video below, I generated an in depth photo of a flower from a really rough sketch.

In a more complicated example below, I’m beginning to construct software that permits you to draw along with your body, then use Stable Diffusion to show it right into a painting or photo.

The end of creativity?

What does it mean that you could generate any kind of visual content, image or video, with a number of lines of text and a click of a button? What about when you’ll be able to generate a movie script with GPT-3 and a movie animation with DALL-E 2?

And looking further forward, what’s going to it mean when social media algorithms not only curate content to your feed, but generate it? What about when this trend meets the metaverse in a number of years, and virtual reality worlds are generated in real time, only for you?

These are all essential questions to contemplate.

Some speculate that, within the short term, this implies human creativity and art are deeply threatened.

Perhaps in a world where anyone can generate any images, graphic designers as we all know them today might be redundant. However, history shows human creativity finds a way. The electronic synthesiser didn’t kill music, and photography didn’t kill painting. Instead, they catalysed latest art forms.

I imagine something similar will occur with AI generation. People are experimenting with including models like Stable Diffusion as an element of their creative process.

Or using DALL-E 2 to generate fashion-design prototypes:

A brand new form of artist is even emerging in what some call “promptology”, or “prompt engineering”. The art shouldn’t be in crafting pixels by hand, but in crafting the words that prompt the pc to generate the image: a form of AI whispering.

Collaborating with AI

The impacts of AI technologies might be multidimensional: we cannot reduce them to good or bad on a single axis.

New artforms will arise, as will latest avenues for creative expression. However, I imagine there are risks as well.

We live in an attention economy that thrives on extracting screen time from users; in an economy where automation drives corporate profit but not necessarily higher wages, and where art is commodified as content; in a social context where it’s increasingly hard to differentiate real from fake; in sociotechnical structures that too easily encode biases within the AI models we train. In these circumstances, AI can easily do harm.

How can we steer these latest AI technologies in a direction that advantages people? I imagine one method to do that is to design AI that collaborates with, fairly than replaces, humans.

This article was originally published at theconversation.com