My grandmother, Claire Hastings, was born within the Twenties on a farm in Armidale, northern New South Wales. That was a comparatively common thing, with just 43% of the population living in cities, compared with greater than 70% now.

She lived in a small picket hut, with a chicken coop out the front and fields out the back. When she and her siblings got here home from school, they helped plough the fields with a horse-drawn plough until sundown.

Little did she know this life would soon disappear. The “second industrial revolution” (of mass production and standardisation) was creating machines to exchange human and horse power. A plough pulled by a tractor could do in hours what took Grandma and her siblings every week.

Bradley Hastings, Author provided

By the time she left school, age 17, she wasn’t needed on the farm. So she as a substitute went to school, became a teacher, got married and raised a family. Now 93, she lives in a comfortable suburban four-bedroom home, enjoys dining at restaurants, and loves going to the theatre and on ocean cruises.

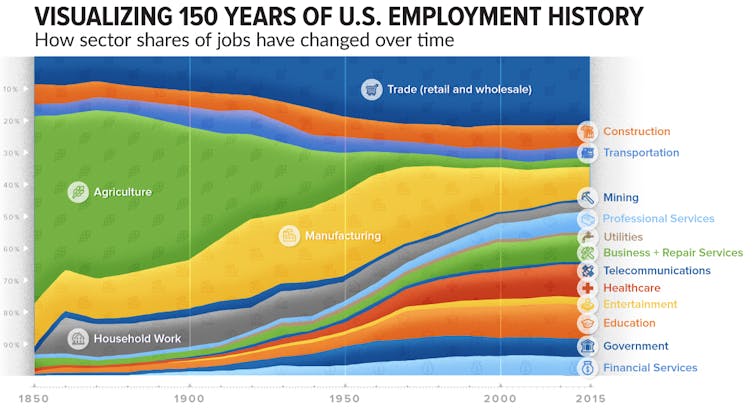

Her story is way from unique. Around the world industrialisation has reduced farm employment enormously. In the United States, for instance, 40% of the

labour force worked on farms in 1920; now it’s about 2%

The lack of those jobs, and their alternative, is price remembering as we now confront the “fourth industrial revolution”, with robots and artificial intelligence tipped to take as much as 40% of the roles now done by humans inside twenty years.

The hit list is long, from drivers and call-centre staff to computer programmers and university lecturers like myself (we face being replaced by AI avatars, delivering animated content online).

But just as disappearing farm jobs didn’t result in everlasting mass unemployment, nor should we fear this next stage of technological development.

Improving quality of life

While industrial farming was not universally embraced as progress, the massive reductions in farming labour over the twentieth century were key to a greater life for most individuals (though poverty and glaring economic inequality still exist).

To cite only one measure, when my grandmother was born the typical life expectancy in Australia was 60 years. Now it’s greater than 80.

The underlying forces driving such advances are twofold.

First, the mechanisation of farming made food cheaper. US data shows the worth of a typical basket of groceries is now about 80% cheaper than a century ago. Similar trends exist for virtually every other consumable product.

Second, spending less on food meant people could spend more on other things. New industries sprang up – automobiles, holidays, health care, finance, fitness and education and so forth. Sectors virtually unknown within the Twenties now employ greater than half of the population.

McKinsey

These recent industries have each underpinned improvements in our quality of life and, crucially, created recent jobs.

As artificial intelligence and robotics develop, services equivalent to banking, insurance and transport will develop into cheaper. As a consequence, we can have extra money to spend on other items – on health and fitness, travel and leisure and possibilities yet to be conceived.

Whatever these recent or expanded industries are, jobs will evolve concurrently quality of life improves for all.

Two lessons from my grandmother

None of this, after all, will necessarily make you’re feeling higher if you have got (and love) a job under threat from automation.

Some lessons from my grandma’s life may help.

First, she didn’t take the changes personally. She understood that times were changing, and that she would should change with them. She embraced the challenge reasonably than being defeated by it.

Bradley Hastings, Author provided

Second, she understood she needed to develop recent skills. At the identical time as farm jobs were diminishing, she saw growing demand for more teachers, underpinned by government regulations requiring children to remain at school longer. So too today education is the important thing for future jobs.

None of us know what the longer term holds. But for our collective future to duplicate the advancements my grandmother has seen over her life, it’s inevitable that artificial intelligence and robots will take over jobs.

I asked grandma if we needs to be nervous. “Life moves on,” she told me.

And so must we.

This article was originally published at theconversation.com