A recent New York Times article released a listing of individuals “behind the dawn of the trendy artificial intelligence movement” – and never a single woman was named. It got here lower than every week after news of a fake auto-generated woman being listed as a speaker on the agenda for a software conference.

Unfortunately, the omission of girls from the history of STEM isn’t a brand new phenomenon. Women have been missing from these narratives for hundreds of years.

In the wake of recent AI developments, we now have a selection: are we going to depart women out of those conversations as well – at the same time as they proceed to make massive contributions to the AI industry?

Doing so risks leading us into the identical fallacy that established computing itself as a “man’s world”. The reality, after all, is kind of different.

A more accurate history

Prior to computers as we all know them, “computer” was the title given to individuals who performed complex mathematical calculations. These people were commonly women.

English mathematician Ada Lovelace (1815–1852) is sometimes called the primary computer programmer. She was the first person to understand computers could do far more than simply math calculations. Her work on the analytical engine – a proposed automatic and fully programmable mechanical computer – dates back to the mid-1800s.

Shutterstock

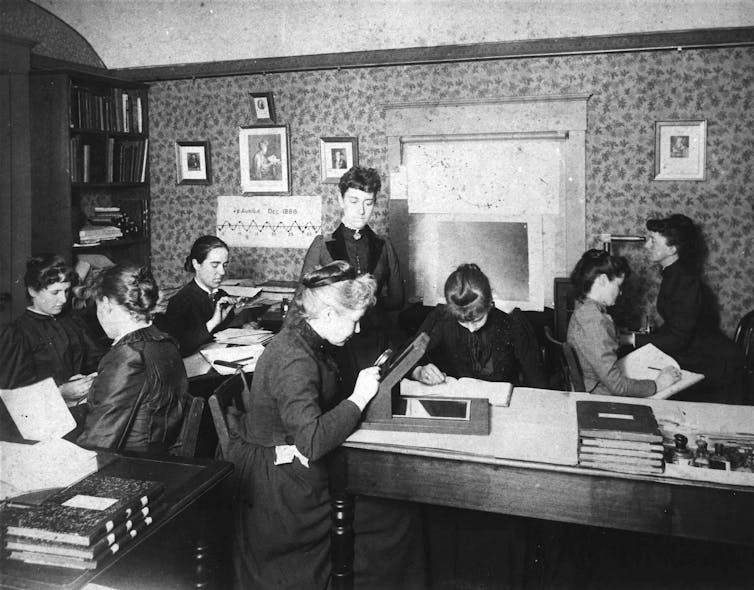

By the 1870s, a bunch of about 80 women worked as computers on the Harvard Observatory. They catalogued and analysed copious amounts of astronomic data for astronomer Edward Charles Pickering (who exploited the actual fact they’d work for less money than men, or at the same time as volunteers).

Wikimedia

By the late nineteenth century, increased access to education meant there was a whole generation of girls trained in maths. These woman computers were cheaper labour than men on the time, and so employing them significantly reduced the prices of computation.

During the primary world war, women were hired to calculate artillery trajectories. This work continued into the second world war, once they were actively encouraged to tackle wartime jobs as computers within the absence of men.

NASA/Bill Ingalls

Women continued to work as computers into the early days of the American space program within the Sixties, playing a pivotal role in advancing NASA’s space projects. One of those computers was Katherine Johnson, who was accountable for quality-checking the outputs of early IBM computers for an orbital mission in 1962.

Many women made significant contributions to computing, yet few were recognised for these contributions – let alone financially compensated. According to Virginia Tech professor Janet Abbate, by 1969 a female computer specialist’s median salary was US$7,763, in comparison with US$11,193 for a male computer specialist.

Woman computers worked behind the scenes, while their male counterparts received recognition, awards and publicity.

Women in AI

Computing and programming are the inspiration of AI as we comprehend it today. At a basic level, today’s generative and predictive AI systems work by analysing large amounts of knowledge and finding patterns in it.

The women who pioneered computing from as early because the 1800s laid the foundations for this work. The work they were doing by hand for greater than a century has now been replaced by machines able to analysing much larger quantities of knowledge in much a shorter time.

This transition doesn’t diminish women’s contributions to the sector of computing and, more recently, AI. Myriad women are doing pioneering work within the AI industry today, including the 12 women named is that this recent Medium article.

From Google’s ex-chief decision scientist Cassie Kozyrkov, to Canadian computer scientist Joy Buolamwini, to OpenAI’s CTO Mira Murati (pictured in this text’s banner image) – these women are helping make AI safer, more accurate, more accessible, more inclusive and more reliable.

Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

And they’re taking these strides despite working in a heavily male-dominated industry. One 2018 study of 4,000 researchers who had been published in leading AI conferences found women made up just 12% of this group.

The impact of omission

The omission of girls isn’t limited to the AI industry, and even to STEM. As historian Bettany Hughes notes, women occupy a meagre 0.5% of recorded history. Clearly, an absence of gender diversity within the workforce is an element of a much larger, systemic problem – one which affects many more people than the individuals being excluded.

In 1983, NASA engineers suggested packing 100 tampons on the Challenger space shuttle for astronaut Sally Ride – for a visit that was one week long. Such an incident is seemingly harmless on the surface. But what happens when gender bias and stereotypes bleed into the design and development of AI?

Research published in 2018 by international non-profit Global Witness found Facebook’s job ad platform, which uses algorithms to focus on users with ads, based its targeting on sexist stereotypes. For example, ads for mechanics were targeted mostly at men, while ads for preschool teachers were targeted mostly at women.

Another 2018 study found computer vision systems reported higher error rates for recognising women, and particularly women with darker skin tones.

A lack of gender diversity in AI has a demonstrated ability to harm and drawback women and, by extension, all of us. While many argue that improving AI training datasets could address the gender gap, others rightly indicate that ladies must also be included in data-collection processes

Breaking the glass ceiling

Speaking on the UN Women’s HeForShe summit earlier this yr, Hugging Face research scientist Sasha Luccioni made a salient point:

AI bias doesn’t come from thin air – it comes from the patterns we perpetuate in our societies.

The recent New York Times article is an example of how each media and industry play a task in reinforcing a establishment that disproportionately favours men. This type of bias does nothing to assist close a persistent and problematic gender gap.

Despite thousands and thousands of dollars being spent to encourage women to take up careers in STEM, these fields are struggling to retain woman employees.

Women’s contributions to AI usually are not insignificant. Failing to acknowledge this could make the glass ceiling seem not possible to interrupt through.

This article was originally published at theconversation.com